It was just announced that Klaus Theweleit will be awarded the Theodor W. Adorno Prize this year so I’ve dug out something about Male Fantasies. I don’t think I’ve ever heard anyone refer to anything he’s published since Male Fantasies, which was based on his PhD thesis and first published in German in the late 70s. Maybe that’s because most of it has never been translated into English. Maybe it’s also for other reasons. According to Wikipedia, his most recent book is a biography of Jimi Hendrix. He’s also written about Jean-Luc Godard, Heiner Müller, football and has published a four volume work called Der Pocahontas Komplex.

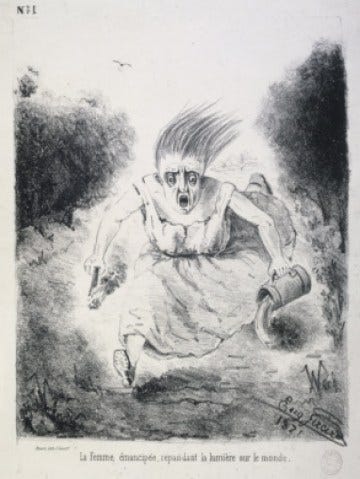

I started writing about Male Fantasies because I happened to be reading it in the same week I read Gay L. Gullickson’s Unruly Women of Paris: Images of the Commune (1996), which discusses the ‘powerful, evil and imaginary’ pétroleuses (women rumoured to have lit fires across Paris during the last days of the Paris Commune of 1871). Both works concern fantastical representations of militant proletarian left-wing women that say more about right-wing masculine fantasies and anxieties than they do about the experiences of actual women (left-wing or otherwise). They both discuss historical moments in which naturalised assumptions about gender were entangled with naturalised assumptions about the organisation of society.

Agents of destruction

Drunk, left-wing, working class, promiscuous – characteristics associated with the pétroleuses in the anti-Communard press are echoed in descriptions of militant leftist women in Klaus Theweleit’s Male Fantasies (the first volume of which appeared in German in 1977). Focusing on diaries and letters written by members of the Freikorps, Germanparamilitary groups of First World War veterans who fought against the newly created Weimar Republic between 1918 and 1923 (many of whom went on to become Nazis), Theweleit explores the relationship between sexuality and politics, asking ‘why, under certain conditions, desiring-production can turn into murdering-production.’

The first chapter of the first volume focuses on the ways these ‘soldier males’ spoke about women, investigating the relationship between misogyny and far-right ideology. The Freikorps officers, he discovers, don’t talk much about their wives. ‘Woman’ is an ideal; actual wives or fiancées are ‘objects of convenience’, ‘marginal figures… child-bearers; silent supporters.’ A soldier’s ‘princess’ is often forsaken for the sake of the Fatherland: ‘Love of women and love of country are at opposite poles’.

The two short sections of Volume 1 that interested me most were ‘Woman as Aggressor’ and ‘Rifle-Women: The Castrating Woman’, which discuss the Freikorps officers’ often lurid and fantastical ideas about militant working class women. As in the example of the Commune, Theweleit emphasises the stark contrast between the imaginary figure of militant sexualised leftist woman and the reality of Red Army nurses. Woman as aggressor is a sexualised but monstrous proletarian figure – ‘a fantastic being who swears, shrieks, spits, scratches, farts, bites, pounces, tears to shreds; who is slovenly wind-whipped, hissing-red, indecent.’ Such women figure as ‘agents of destruction,’ their violence and lasciviousness linked to their class position.

‘The fantasized proletarian woman’ is often armed; she may be one of the ‘sadistic, grinning rifle women’ of the Red Army’ or a ‘bestial foe [who] has desecrated defenceless wounded men’. Sexual and political anxieties wrap themselves around her gun. ‘Just like waitresses, barmaids, cleaning women, prostitutes, dancers, and circus performers the rifle women are given only first names.’ Theweleit cites a passage – almost dream-like in its vivid surrealism – in which a Spartacist woman is depicted ‘hair flying, packing pistols, and riding shaggy horses [presenting] an image of terrifying sexual potency.’

‘The sexuality of the proletarian woman/gun slinging whore/communist is out to castrate and shred men to pieces,’ Theweleit declares. One account describes a woman who proclaims: ‘we want guns, grenades, revolution!’ and is represented as drunk and sensuous; her stained silk dressing gown a symbol of her seductive yet dangerous moral depravity. " Shred them to pieces and pulverize them with dynamite," one of these threatening but wholly imaginary female revolutionaries declares, which Theweleit reads as an anxiety the author has about the leftist woman’s desire to annihilate all men on the Right. As he discusses, in Nazi propaganda the image of the First World War Red Army rifle woman resurfaced and was presented as if it had posed a real threat – take this example from a 1935 primer:

It is well-known that there were rifle-women behind the Red lines who were under orders to stop the troops from falling back, or if the retreat could not be stopped, to shoot at their own people. The rifle-women were the sort of cruel furies only Bolshevism could devise. While the heart of one of the men of the Red Guard might be moved to pity at the sight of suffering innocents, those women were bestialised and devoid of all human feeling.

Here, the woman becomes not only a figure who transgresses traditional gender roles; she is situated outside humanity as such. She isn’t simply masculine but becomes animalistic.

Everything flows

Theweleit is obsessed with liquidity. He sees liquids flowing everywhere in the documents produced by the Freikorp officers. The Bolshevik masses surge like ‘floods, torrents, raging water’. Some characteristic verbs: inundate, engulf, pour, flow, swallow up, stream, gush, rage, flood, boil, bubble, seethe, whirl. (He likes lists and so do I).

The officers abhor everything that gushes and rushes, particularly the ‘Red floods’ of Bolshevism. Revolution figures as liquification. And the right-wing men want to dam it all up, contain it, bring it to a halt. They proclaim ‘[d]eath to all that flows’. (For some reason I find myself picturing Arnold Schwarzenegger as Mr Freeze). This leads Theweleit to Freud’s limitless oceanic feeling and then to the surging qualities of libidinal desire (as described in Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus, which was published shortly before his book and from which he drew much inspiration). Then he moves to experiences of boundlessness and, finally, to the release of tension associated with orgasm. Theweleit distinguishes his understanding of ego development from Freud’s, rejecting an account focused on the Oedipus complex in favour of an argument emphasising instead the discipline of the body associated with military drills and parades: a bounded, homogeneous, synchronised mass entity emerges. Man is the nation is an impermeable block.

These Freikorps men were repressed, terrified of sexual abandon, and this fear was linked to their fear of women (which is in turn, as he discusses in detail in Male Fantasies’ second volume, linked to a fear of the mass). The only time they let themselves dissipate was in a deathly confrontation with a male enemy with whom they identify: ‘he melts into the blood of a man of his own kind. His ecstasy takes the form of a “blackout”: perception of an end to the torment of existence as a man for whom some form of coupling is indispensable, yet who never experiences the flowing of pleasure.’ Death takes the place of sex (or maybe death is sex).

Women in the sources Theweleit analyses are porous and are also associated everything that flows; they have permeable boundaries and threaten the boundaries of others. He veers off from his historical documents towards the end of the first volume of Male Fantasies to discuss mythic and literary representations of woman and takes a detour via ancient and early modern European history. Theweleit’s anachronistic use of illustration – the text is interspersed with an array of images including advertising images from the Third Reich, election campaign posters from the GDR in the 1970s, late nineteenth-century English paintings, movie stills from the Golden Age of Hollywood and Medieval engravings – similarly suggests that the figure he is describing is not specific to the historical and cultural moment he is describing, but a kind of archetype. The implication is that characterisations of masculinity and femininity are, if not exactly transhistorical, then at the very least extremely long-standing and resistant to change. The image that he is concerned with excavating is of ‘woman-in-the-water; woman as water, as a stormy, cavorting, cooling ocean, a raging stream, a waterfall; as a limitless body of water that ships pass through, with tributaries, pools, surfs, and deltas; woman as the enticing (or perilous) deep, as a cup of bubbling body fluids; the vagina as a wave, as foam…’ You get the idea.

Murky waters

The final sections of the chapter discuss dirt and contamination and it is here that he returns to his primary sources and to the explicitly anti-communist political content with which the chapter began. Headings include: ‘The Mire’, ‘The Morass’, ‘Slime’, ‘Pulp’, ‘Shit’, ‘Rain’. Images of national decay are linked to descriptions of menstruating sex workers. Men of the right characterised the left as filthy and saw leftist bodies as insufficiently contained: they ooze excrement and pus and menstrual blood. They weep ‘secretions from the different orifices of the lower body’. Freikorps men will only consent to transcend boundaries when blacking out or dying; they ‘couple’ with themselves in combat and their ‘own struggle for survival [becomes] a direct onslaught on femininity.’

I was struck by a surprising proximity to Anne Carson’s discussion of women in myth. According to Carson, women in myth transgress boundaries and have no firm boundaries of their own. ‘Pliant, porous, mutable’, they are unable or unwilling to maintain a fixed form. They metamorphose, shrink, cry, leak, open things, and are generally sieve-like. Their emotions are linked to wetness and dissolution (of men): ‘Emotion is a liquid or liquefying substance that pours into a person and dissolves him.’ Women in myth are dirty, ‘pollutable, polluted and polluting.’ Carson’s description of erotic desire in myth which is ‘said to melt, flood, soften, loosen, boil, broil, roast, drown and disintegrate’, uncannily recalls Thewleit’s litanies of liquification. But this similarity gestures towards a paradox in Theweleit’s discussions of militant proletarian women because Carson’s descriptions apply to all mythological women rather than to a deviant militant subset.

The weapon-wielding woman who threatens to shred men to pieces is simultaneously the antithesis and epitome of the feminine. Theweleit reads the woman as aggressor in terms of castration anxiety. The women in the narratives he discusses pull weapons from beneath their clothing and cut off protruding body parts. He insists that the imagined threat is not vaginal but phallic: ‘we are dealing with the fantasy of a threatening penis.’ But these men only assign penises to certain types of women: violent leftist women. As such, he claims: ‘The men experience “communism” as a direct assault on their genitals’. The threat these women pose is more than just castration, but total annihilation understood in political terms. Within the space of a few paragraphs, however, Theweleit connects the specific image of a politically violent woman with a phallic weapon with erotic woman in general; both figures are examples of ‘nature perverted’ and both also seem to respond to anxieties about the changing social status of women understood as a transgression of the natural order. Women don’t need to be communists with a penis-gun to threaten men after all. And those women were figments of the male imagination anyway. Indeed, elsewhere Theweleit notes the preponderance of the trope in the Freikorps corpus that ‘Women are all the same.’

The image of the militant leftist woman who confounds nature, takes on masculine attributes and transgresses feminine norms both defies and defines womanhood. (She is an abject woman, though in some sense all women are understood as abject. She is mad, though in some sense all women are understood as mad etc). In Gender and the Political Amanda Third notes of the figure of the female terrorist that she is both ‘hyperterrorist (and therefore not properly feminine) and simultaneously hyperfeminine (and therefore not properly terrorist but nonetheless highly dangerous).’ The terrorist woman may be seen to violate nature by being violent, overtly sexual, non-reproductive or a bad mother, yet attributes understood as naturally feminine (even if viewed negatively) - such as irrationality and heightened emotion - are also applied to her, while a man who commits an act of political violence tends to be viewed as a rational actor even by those who condemn his actions.

Animate subjects

In Theweleit’s sources ideas of women are often paired with representations of violence. Women are rendered ‘cold and dead’ in these men’s descriptions (and are sometimes literally murdered); they become ‘inanimate objects’. Women are both desired and feared; they might be asexual and nurturing (a maternal nurse) or erotic and threatening (a sex worker) but these two types of imagined woman must both be ‘rendered lifeless’, the first through objectification, the second through physical violence: ‘it is the aliveness of the real that threatens these men.’ Threatening women are killed and mutilated. In death they acquire an erotic aspect. He writes: ‘The "red roses" of her sex only blossom from the wounds on her dead, deformed, opened-up body.’ These dead objects can then take on new forms:

Reality, robbed of its independent life, is shaped anew, kneaded into large, englobing blocks that will serve as the building material for a larger vista, a monumental world of the future: the Third Reich. In constructions of this kind, with their massive exteriors and solid forms, everything has its proper place and determinate value.

If the liquidity of sexualised woman threatens the solid structures and boundaries of the man and of the masculine nation, then here the suggestion is that if controlled and harnessed those same liquids - blood and pus and vaginal discharge - could become the basis for a new solid world. [Insert one hundred upside down face emojis here]. It is all a question of power and domination.

Yet the critique levelled at Theweleit by West German critics and particularly by feminists when his book was published was that because he only examined male fantasies about women he also reduced women to an image, thus excluding the experiences of real historical women from his analysis. His image of ‘englobing blocks’ says nothing about actual violence against actual women, neither direct physical violence nor the numerous slow violences of patriarchal oppression . He castigates right-wing men for objectifying women but is only interested in how this phenomenon relates to fascistic ideology more generally. Violence becomes strangely abstract: the objectification of woman is merely a stepping-stone on the way to a particular fascistic conception of the nation. He is not interested in restoring women to their place in this history nor in asking about their experiences and fantasies. As a generally sympathetic reviewer Lutz Wiethammer noted (in a piece that was translated into English in the History Workshop Journal in 1979): ‘he says that men and women ought always to be considered in relation to each other — but then goes ahead and investigates only men, and their image of women. Women as people in their own right are barely present in his work; they are there as hypothetical constructs.’

In Sex After Fascism: Memory and Morality in Twentieth-century Germany (2007) Dagmar Herzog argues that Theweleit’s book should be understood in relation to the historical context in which it was written. In the context, that is, of the sexual revolution. It was written in the disenchanted aftermath of the student and worker’s movements of 1968, when many on the left began to question their previous insistence on the entanglement of the personal with the political. Theweleit had been an active ‘68er. ‘Theweleit’s book’, Herzog argues, ‘was in its own way an effort to recapitulate and retrieve much of 1968’s original impetus and to re-establish a strength of connection between sexuality, leftist politics, and the Nazi past that had started to become frayed.’ The book was a huge success, she writes, a ‘blockbuster’.

Absent from Herzog’s account of the reception of Male Fantasies is any discussion of how his characterisation of militant leftist women chimed with representations of West German woman militants at the very moment his book emerged in public. 1977, the year Theweleit’s books were first published, was also the year in which the militant activities of the Red Army Faction peaked in West Germany. Over 50% of the group were women. (In 2001 Theweleit released a double CD called Das RAF Gepenst. I haven’t listened to it but it looks as if it reflects on his own experiences of the 60s and 70s and the turn to violence. The blurb proclaims: “A spectre is haunting Germany, the spectre of the RAF…”).

Third claims that during the 1960s and 1970s the female terrorist was automatically assumed to be a feminist. The emphasis on the participation of women in militant activist groups and the demonisation of those women was tied to a more general backlash against feminism: terrorism was defined as a symptom of excessive emancipation. In the mainstream West German press women’s acts of political violence were framed as either self-motivated (performed to impress a dominant male lover) or pathological, rather than political. As Patrizia Melzer discusses, grassroots left-wing feminist publications argued that the ‘overall image that ‘women who resist are crazy’ results in a psycho-pathologizing of militant women that ‘completely deflects from their political motives’.’

(Not) All Men

Despite criticisms by feminists at the time, Herzog claims that ‘Theweleit’s message to the heterosexual men of his own generation was that they should not resist feminism.’ Theweleit warns men on the left not to succumb to the misogynistic fear of sexual abandonment that he associated with proto-fascist masculinity. Don’t be a block, ooze! He expresses anxiety that being a misogynist might not be the preserve of men on the right at all (fair enough), but for him it therefore follows that all men (or maybe just straight white German men?) are basically proto-fascists, which is quite a leap.

Theweleit’s thesis is premised on a connection between hatred of women and violent nationalism but he can’t quite rid himself of the anxiety that there is nothing exceptional about the misogyny of the (proto)-fascist men he discusses. Just as the weapon-wielding Communist woman soon collapses into woman as such, so the right-wing ideologue collapses into all men. Theweleit poses an uneasy question: ‘Is there a true boundary separating “fascists” from “nonfascist” men?... Or is it true, as many feminists claim, that facism is simply the norm for males living under capitalist-patriarchal conditions?’ He argues that current conditions are already a form of fascism, not latent or potential but actual:

We need to understand and combat fascism not because so many fell victim to it, not because it stands in the way of the triumph of socialism, not even because it might return again; but primarily because, as a form of reality production that is constantly present and possible under determinate conditions, it can, and does, become our production. The crudest examples of this are to be seen in the relations that have been the focus of this first chapter, male-female relations, which are also relations of production.

But what then does he think fascism is exactly? Just because a man with professed ‘progressive’ views might also be a misogynist doesn’t mean that his misogyny is identical to that expressed by someone on the far-right, nor does the misogyny of either have a straightforward connection to racism or other forms of hatred (of which he makes no mention here). Is he saying that ‘male-female relations’ are analogous to fascism, are fascism or produce fascism? The possible implications are bemusing. Do fascist women simply not exist? Are all men white? Are all white men white supremacists? How can a different reality be produced? Is reality itself founded in fantasy? Am I asking stupid questions and being too literal? Maybe. But it seems that conflating patriarchy with fascism risks producing just another kind of ‘englobing block’ into which actual people (and actual struggles against interconnected but distinct forms of oppression) disappear.

-

Anne Carson, ‘Dirt and Desire: Essay on the Phenomenology of Female Pollution in Antiquity’, Men in the Off Hours (London: Cape Poetry, 2000),

Gay. L Gullickson, Unruly Women of Paris: Images of the Commune (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996)

Dagmar Herzog, Sex after Fascism: Memory and Morality in Twentieth-century Germany (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007)

Patrizia Melzer, ‘”Death in the Shape of a Young Girl”: Feminist Responses to Media Representations of Women Terrorists During the ‘German Autumn’ of 1977’, International Feminist Journal of Politics, 11, 1 (2009), 35-62

Lutz Niethammer, ‘Male Fantasies: an argument for and with an important new study in history and psychoanalysis’, History Workshop Journal, 7, 1 (1979) 176-186

Klaus Theweleit, Male Fantasies, vol. 1: Women, Floods, Bodies, History, trans by Stephen Conway with Erica Carter and Chris Turner (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1987)

Amanda Third, Gender and the Political: Deconstructing the Female Terrorist (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014)