This post that isn’t about psychoanalysis at all, sorry. Instead, it’s about Christina Stead’s novel I’m Dying Laughing, which I read a while ago after reading Caitlín Doherty’s essay about it for New Left Review’s Sidecar.

In her 2019 introduction to the reissue of The Romance of American Communism (first published in 1977) Vivian Gornick expressed regret that her romantic attitude to the former members of the Communist Party USA she interviewed led her to omit some of their ‘complexity’, which seems like a euphemism for cruelty:

there would be no presentation of the branch leader who loved humanity yet ruthlessly sacrificed one comrade after another to party rigidities; or, equally, the section head who could quote Marx reverentially by the hour, then call for the expulsion of a CP member who had served watermelon at a party.

Caitlín Doherty contrasts Gornick’s representation of Communist Party members with those who populate the posthumously published unfinished novel I’m Dying Laughing by Christina Stead about which Gornick herself wrote admiringly. Stead’s works, Doherty observes, ‘stubbornly refuse to coalesce into a single political message.’

The novel follows the fates of Emily and Stephen Howard, a married couple it would be very easy to imagine serving watermelon at parties. They are Party members who move to Hollywood in the forties, leaving for Paris after they are accused of being ‘wreckers, saboteurs, Trotskyists, bastards, petty bourgeois poseurs, rich crackpots,’ after deviating from the Party line on maintaining a united front during the Second World War, just as the clouds of McCarthyism are beginning to gather.

Emily and Stephen want to be rich and to eat well. Stead’s characters talk and talk and eat and eat: ‘They all began to shout and crow and to throw dates and events at each other.’ The characters converse endlessly – sometimes earnestly, sometimes flippantly – about money and families, war and genocide, Lenin and literature. Gornick remarked that there ‘is no more accurate imitation in American literature of the sound and feel (and length!) of that kind of talk.’

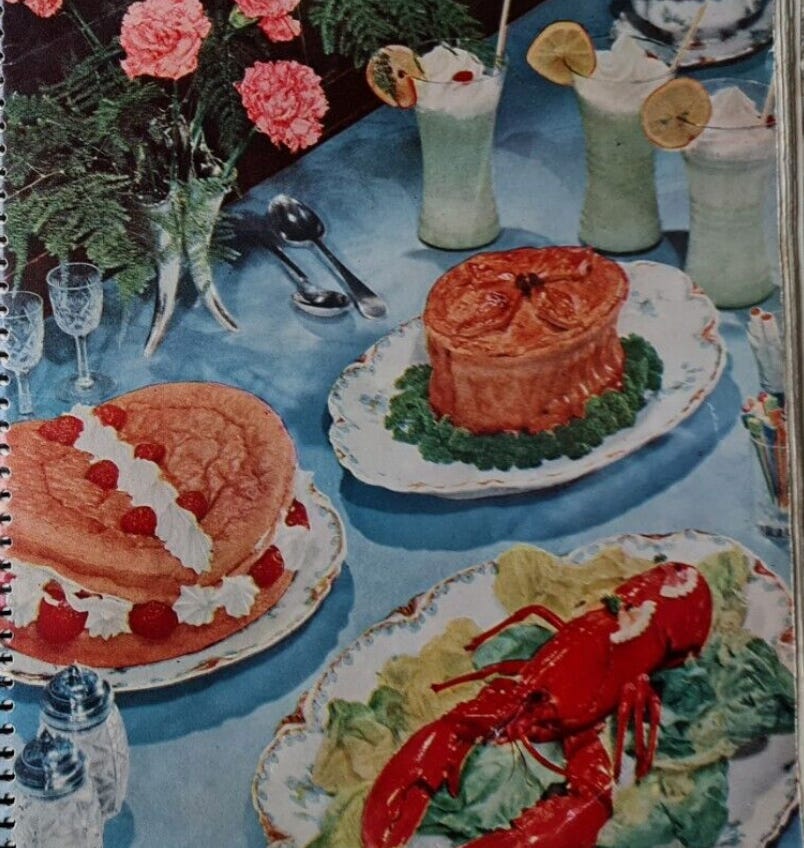

Although the novel has the structure of a tragedy its tone often tips into farce. Emily wants to be a serious political writer but remains the ‘humorist’ author of popular family sagas: ‘“A girl wanted to go on stage and recited Lady Macbeth’s speech. The talent scout said she would make a wonderful comic. Well, that’s me.”’ Lady Macbeth mimes washing her bloody hands in her sleep muttering, ‘Hell is murky’, while Emily, predicting her imminent expulsion from the CPUSA, gorges herself on ‘melted butter, sweet corn, mashed potatoes, mushroom cream sauce, hot popovers, chocolate sundaes, glazed orange slices and chicken supreme.’ Gornick described herself and her peers in the women’s liberation movement becoming ‘walking embodiment[s] of the gap between theory and practice’, a gap Emily constantly frets over. She fills her body with luxurious foods, while wrestling out loud with her compulsion to do so: ‘“I feel ashamed before real revolutionaries like some of you, who would live on grass rather than give up.”’ In Stead’s depiction, life as an American Communist is murky. Hell is other communists. I’m Dying Laughing is a murky book. As Doherty writes, it is ‘the final work of an author who has lost interest in resolution. For all the political talk in the book, its political lessons are thorny and demotivating where they can be said to exist at all.’

Gornick describes how, in the decades Stead was working on I’m Dying Laughing, a gulf opened between her intentions for the book and her increasingly unwieldy drafts. But this gulf is not identical to the gap between theory and practice identified by Gornick. Stead eventually accepted that she’d lost her way with the book, but Emily and Stephen have lost their ways too. It’s hard to impose a definite meaning or satisfying teleological structure on lives characterised by conflicting desires and wavering commitments, who have lost their connection to an ideological worldview that imagined history moving inexorably towards proletarian revolution; people who can’t decide if they want to fight for a luxurious life for all or just would rather retreat into a life of luxury for themselves. Gornick characterised Communist turned anti-Communist Arthur Koestler’s self-castigating autobiography as saying of his abandoned Communist commitments: “I can taste the ashes but I cannot recall the flame” (and also incidentally likens him to Lady Macbeth). She quotes Stead declaring that her intention was for I’m Dying Laughing ‘to go on from fire to more fiery to fierier still.’ Instead the book not only alternates between flames and ashes, but relies, as Doherty notes, on ‘the comedy of incongruity’, swerving from noble acts of resistance to banana whips, from heated discussions of Kautsky to lobster mousse.

Gornick conveys how daily lives in the Party were infused with the grandeur of a global struggle (something I previously wrote about in collaboration with Larne Abse Gogarty), whereas Stead more often shows serious discussions of political causes and historical events accompanied by pettiness and triviality. The novel is both bathetic and pathetic.

In exile in Paris in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, the Howards encounter people who had been active in the Resistance: former activists in underground groups who hid Jewish children during the occupation and Party members who had survived concentration camps. Emily marvels at the courageousness of these people, but is also slightly disappointed by the apparent ordinariness of their experiences, by their lack of glamour and grandeur: ‘“the way you say it, it is not exactly spectacular; they would not put it in the movies.”’ Early in the novel, Stephen, who comes from a wealthy family, had justified his love of luxury as consistent with his political beliefs: ‘“I don’t want to live with heroes of labour… I’ve seen lots of them. Starvation and struggle are no good for the soul; nor the stomach. What are we fighting for?”’ By the end, Emily revealingly opines:

How strange that the rich, the bourgeoisie should have such a beautiful life! What a dilemma! What a puzzle! For surely their minds and lives are finer than those whose dreams are of back streets, garbage cans, vacant lots filled with rubble, howling landlords, roaches in the kitchen! What horrible dreams they are!

She lives her beautiful life and stops fighting for a beautiful life for all. As the couple careen towards a final capitulation that sees them abandon the cause entirely to turn people over to the CIA, Emily compares their position to a former member of the Resistance who has now been shunned: ‘“No-one would even talk to him nowadays with his automobile lined with white velvet, his house of Vita glass, his gold-plated bathroom.”’ She laughs (as usual): ‘“What a glorious, gorgeous monster! And helped the Resistance too. Can we too not perhaps enter the annals of the red register as gorgeous monsters, human, all-too-human… adoring the fine life; but still faithful in our hearts.”’ What does it mean to be faithful in your heart, while doing nothing, while fighting for nothing? Well, nothing. Gornick’s Communists are ‘awesome, hungering, deeply moving’. By the end of I’m Dying Laughing Emily has become ‘teasing, trifling, annoying’.

Gornick presents the appeal of Communism in universal terms, as answering a generalised human need to find meaning the meaningless universe, but she presents the antagonisms that arose within the Party as specific to that dogma-infused context. The grandiose explanations of the world that infused Communist lives with meaning were, for Gornick, also the origins of dogmas that caused people to demand impossible standards of behaviour from themselves and others. Stead’s novel seems less sure. By the end of I’m Dying Laughing, Emily argues that all humans are monstrous as a way of justifying her own monstrous behaviour to herself.

Back when everyone on Twitter was arguing about working for Lockheed Martin I thought of Stead’s novel.