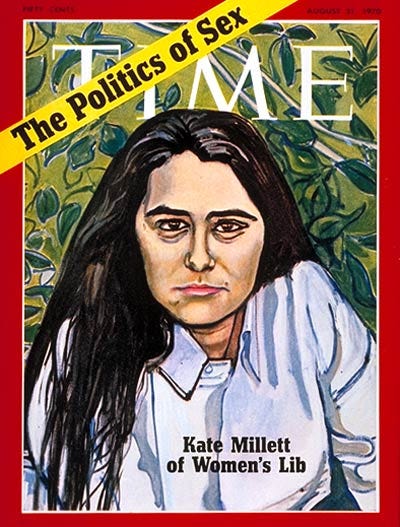

Kate Millett’s autobiographical tome Flying was published in 1974, written in the 18 months following her sudden lurch into the public eye following the publication of Sexual Politics in 1970 and in the wake of the furious debates around sexuality engulfing the women’s liberation movement. A portrait of Millett by Alice Neel graced the cover of Time magazine in summer 1970 with an accompanying story that cast Millett as ‘the voice of the movement’ and as feminism’s Mao. A subsequent piece followed in December of the same year entitled ‘Women’s Lib: A Second Look’, which outed her as bisexual and participated in an emerging narrative that associated women’s liberation (pejoratively) with lesbianism. As Victoria Hesford discusses, after the publication of the Time article, Millett found herself caught up in arguments around ‘lesbian visibility and straight respectability’ raging within the movement, which left her ‘in the headlights of identificatory pressures that demanded of her a representativeness. She had to be one thing or another: lesbian icon of the movement or its bisexual betrayer’.

Sexual Politics had been lauded for demonstrating that sexual life was not cordoned off from the realm of the political, for arguing that psychology and interpersonal relationships were ideologically shaped, but Millett’s own foray into first-person explorations of such themes was received disdainfully by critics who dismissed it as being tiresome in length, incoherently structured and self-indulgent in its preoccupations. Hesford contends that ‘Millett was practising the politics of women’s liberation by focusing on the quotidian and the ineffable’, but that the ‘politics of women’s liberation were absented from the field of interpretation’ in Flying’s reception. Yet Hesford’s assertions gesture to the ambiguity of the phrase ‘the personal is political’ as Flying seems less interested in demonstrating the systemic underpinnings of personal experiences and sexual relationships than it does in demoting the quotidian back to its place outside of history proper. By refusing to subject the flow of events and feelings to any kind of structural analysis, Millett implicitly suggests instead that sometimes a life is just a life. For Hesford, Millett’s decision to write about her life in all its mundane detail was ‘political as well as… aesthetic’, in tune with the women liberation movement’s insistence that daily activities and feelings should be treated as political issues, but Flying was not political in a more active, outward-looking or agitating sense.

Flying flies between places and times: from Millett’s childhood in Minnesota to bars in Japan (where she studied sculpture in the late 1950s and met her future husband Fumio Yoshimura), from her Bowery studio to the various university campuses at which she studied and later taught, from her farm near Poughkeepsie (where she lived with a feminist collective) to political meetings and kitchens in London (where she spent time during the tumultuous period charted in the book). She flies between speaking engagements where she writes in notebooks attempting to compile ‘glimpses of self snatched on planes’. Millett describes her experiences of wrestling with the fragments that would become the book and recalls discussions with friends about her conception of it: ‘surely it would be useful for others to hear how one actually thinks, what is experienced by the persons thrashing about hoping to bring change into being.’ She records the feeling of not being able to convey her thoughts in writing or to capture the events unfolding around her: ‘the devouring present historian in me is a monster. If only I could bug my own head, go direct from brainwaves to paper…’ She describes assembling scraps of paper, attempting to impose some kind of unity upon ‘the scribble of my madness, a collage of the winter evil, splinters of the explosion written furtively on airplanes’. Ultimately, however, the book remains scribbly, collage-like and splintered – an impressionistic, sprawling exercise in narrating the day-to-day blur of life without a coherent ‘I’ around which the haziness might come into focus but without the detached staccato modernist sheen such a description might imply.

On a plane again, she describes feeling cowardly about her writing, afraid to reveal herself in it, anticipating the kinds of criticisms that would indeed greet the book’s eventual publication: ‘…is it too disparate? Mere tidbits of thought, memory, grasshopper trivia.’ Though Sexual Politics included a long section attacking Freudian psychoanalysis, here Millett seems to embrace something akin to the psychoanalytic technique of free association, with nothing too banal or trivial to be considered irrelevant. Millett claims to have had the idea ‘to treat my own existence as documentary’ (among other things the book documents her involvement in the collaboratively produced documentary film Three Lives). Even in the early stages of writing she is already imagining how the project will be torn apart – ‘my head is full of critics ridiculing’ – though a friend urges her not to self-censor: ‘“Put everything in and they’ll murder you again, even and especially the movement ladies who murder each other until I am exhausted with the spectacle.”’ As well as anticipating attacks from other feminists, she seems to have a kind of internalised left-wing masculine superego who insists her work isn’t properly political: ‘just a silly broad, no notion what she really means.’ She expresses the anxiety that her book ‘sniffs of the confessional’ to a friend who replies that it is a regrettably ‘whiny form’. Earlier she proclaims: ‘I hate confessionals’. It seems redundant to skewer a book for being a whiny confessional that so bluntly confesses to being one.

Millett documents how she negotiated her own status within the movement, as well as her relationship to the movement. She often speaks of ‘Kate Millett’ as a kind of character, bemoaning becoming a ‘prisoner of that monster created in my name’, a ‘scary mannequin… Someone else’s invention’. As she snaps in one conversation, ‘“you are aware that I am not Women’s Lib? Personified? In the flesh?”’ She expresses her desire to write something that’s just about her own life without the expectation it speaks for all women or all feminists: ‘Are you a pawn? Do you belong to the movement not yourself? I hope not. Damned little good to it if I’m not my own woman first. Who are you then? I am all the things I am. One of them is a woman in the movement.’ As she shuttles between public appearances she feels alienated, bored and exhausted by her spokesperson status, a role she is expected to inhabit and called upon to perform but for which she was also denounced: ‘You are piece of shit, you are a star.’ Resented and resentful, ‘used and used up’, she worries that the tedium she associates with being constantly questioned on behalf of the movement and the sometimes faltering convictions with which she formulates her answers in public makes her traitor: ‘All I can say are platitudes more tedious with repetition, calling for a revolution vague beyond fantasy, remote beyond hope. Here in the bosom of the faithful who have goodness to speed rather than to doubt.’

Flying also recounts arguments between Millett and other women’s libbers, claiming she was ‘assassinated for the crime of individualism.’ She describes the cruelty displayed between women in the movement, of women ‘exhausted by abuse, tired, discouraged’, weeping in corners like bullied school children or ‘battered into trauma’ by consciousness raising groups. Yet her reflections are fraught with ambivalence, observing that consciousness raising invoked joy alongside fear. In one episode she recounts sharing her frustrations with her ‘star’ status with a group of women. She expects them to attack her but instead finds ‘they give me the joy of being understood, that wonderful euphoria of first meetings when a woman finds all her crazy irritations shared by others, her private grievances revealed as part of the social fabric.’ ‘“We are sisters”’, she implores in one confrontation. ‘“Sisterhood is bullshit”’ is the retort. In this exchange she appeals to bonds of friendship that exist beyond the movement: ‘“If we can’t hold on to that the political thing can become insanity.”’

Feminism is invoked here as the barrier preventing friendship between women. Abstract political convictions could obstruct concrete interpersonal relationships that were forged precisely in contexts that sought to identify the ways the political was not abstract or separate from individual lives at all. Women who had attempted to weave an alternative social fabric together soon found it fraying around them. But one of my favourite phrases in Flying acknowledges that this shared experience of unravelling paradoxically created its own fraught bond, which Millett calls the ‘solidarity of disappointment’.